Make the Web a More Colorful Place!

A guide to using new color spaces & formats with OddContrast

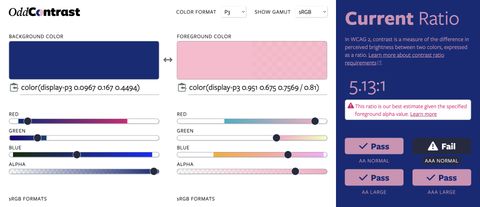

OddBird’s color tool not only checks contrast ratios, but supports the new CSS color formats and spaces.

Transmitting objects between web processes and worker processes is a requirement of many modern web apps. Given that the safest way to do so is to use a serialization format that only includes primitive data types, how can we send custom objects around?

Many Django apps need some kind of out-of-band processing. Perhaps you have to make calls to a separate API server, and don’t want to nest the latency of HTTP calls. Or perhaps you need to perform a slow and complex post-processing step on user-submitted data. Whatever it is, you can’t just put everything in your web processes. Some things demand worker processes consuming tasks from a queue.

Typically we use Celery for this, though increasingly Django Channels is emerging as a viable option. In either case, there are issues that arise from the use of a task queue broker; because of the indirection that the broker (be it an AMQP server or Redis or whatever) introduces, you can’t share memory. Without sharing memory, you can’t share in-memory objects. So, you somehow have to get data between the web requests and the worker processes.

If it’s just primitive data, that’s fine, you can serialize it. But what if it’s not? What if you have a Django model that you want to pass to a task? This is hardly an uncommon need, but there are a few ways to approach the problem.

First, of course, you can use the pickle Celery task serializer. This

isn’t terrible, but pickle does open you up to some security concerns.

You can mitigate them, but unless you feel confident that you know what

you’re doing, it’s best to avoid exposing yourself to them in the first

place. In the same way that you can sanitize all your database inputs

and assemble DB queries through string concatenation – but would be

well-advised to use prepared statements – you can ensure that

everything that touches pickle is adequately sanitized. I, for one,

prefer to avoid using it, and save myself the worry.

To ensure we don’t risk executing arbitrary code, we can tell Celery to use the JSON serializer:

CELERY_TASK_SERIALIZER = 'json'But now we can’t pass full Python objects around, only primitive data. If we try to pass something that can’t be JSON-serialized, we’ll get a runtime error.

(This has another use, incidentally: it frees us to make our worker and web processes in different languages. That’s beyond what I’ll talk about here, but it’s worth thinking about!)

But, we want to pass our models around! How can we do this?

The usual approach is to define tasks to take the model ID as a

parameter, and just pass that. If I need a Foo, I’ll have a parameter

foo_id that I pass to the task. Then in the task, I’ll access the DB

and pull that Foo instance out.

That’s fine. It doesn’t quite cover all situations, though.

This is a case I’ve run into. I had a task that had to be run on three

different models (specifically, Question, Answer, and Comment)

that all had a body attribute. I could duck-type my way around this

under most circumstances, but when it came to passing them through the

task-broker barrier, I had to have some way to know just what type of

model I was working with.

There are three obvious approaches:

The first, which is also the worst, is to have a version of the task for each type. You might call this “the poor man’s parametric polymorphism,” but it isn’t really polymorphism at all, and it tends to lead to code duplication. Don’t do this.

(Yes, you can avoid much of the code duplication by well-decomposed tasks and functions, and making a series of shims that make assumptions about the types of the arguments. Still don’t do this.)

Alternatively, you could add three (or however many) different arguments to the task:

@task()

def some_task(foo_id=None, bar_id=None, baz_id=None):

if foo_id is not None:

obj = Foo.objects.get(pk=id)

elif bar_id is not None:

obj = Bar.objects.get(pk=id)

elif baz_id is not None:

obj = Baz.objects.get(pk=id)

else:

# Do some error logging and return.

return

# Operate on objThis is tolerable, but it adds a lot of boilerplate. You get a

function signature that increases in length as the number of possible

types increases, and you get a long if/elif/else chain that

increases at the same rate. Neither of these have much to do with your

task’s logic, but they take up a lot of brainshare.

Also, with both this approach and the previous approach, you have to know at the call site what sort of ID you’re passing in. This is a mixed blessing. It makes the code very legible, but it does impede managing things programmatically.

The third option – my favorite – is to simply tell the task what model you need:

from django.apps import apps

@task()

def some_task(model_name, model_id):

Model = apps.get_model('django_app_name.{}'.format(model_name))

obj = Model.objects.get(pk=model_id)

# Operate on objNote the crucial piece here: django.apps.apps.get_model. It takes a

model identifier, which is django_app_name.ModelName. The

django_app_name is the last dot-separated part of whatever you put in

INSTALLED_APPS. The ModelName is the name of the class in the

models module in that app.

For added delight here, you can even get the model name automatically in a mixin to your models:

class SomeMixin:

# Assuming that you want to trigger the task on save:

def save(self, *args, **kwargs):

ret = super().save(*args, **kwargs)

some_task.apply_async((

self.__class__.__name__,

self.pk,

))

return retAs a final word to the wise, it’s worth noting that this entire database-mediated approach opens you up to certain timing risks. Data can skew, and you expose yourself to potential race conditions. Sometimes that’s not an issue, and sometimes it’s just an acceptable cost. But in any case, it’s worth keeping in mind.

Perhaps you have business-logic class instances which are never stored in the database[1]. If you can’t, won’t, or don’t want to use the DB as a persistent store for your data – which you then inflate into a full object – there are other ways to pass objects through the task-broker bottleneck.

They all boil down to separating the primitive data from the methods and logic. Think of it like passing the record or struct through, not the whole class.

So if that’s the goal, you could make custom JSON encoders and decoders that know how to traverse your classes. But that’s a pain. Let’s see if we can write as little code not related to our actual business logic as possible.

One approach I like is to use the attrs library. It lets you define your business logic class like so:

import attr

@attr.s

class SomeClass(object):

foo = attr.ib()

bar = attr.ib()

def some_method(self):

pass

And then you can easily serialize an instance:

import attr

inst = SomeClass(foo={'hi': 'there'}, bar=SomeClass(foo=1, bar=False))

attr.asdict(inst)

# {'bar': {'bar': False, 'foo': 1}, 'foo': {'hi': 'there'}}And just as importantly, you can pass that serialized data to the task, and inflate it:

def some_task(some_class):

inst = SomeClass(**some_class)How have you handled object serialization in your projects? We’d love to hear your thoughts on Twitter, or through our handy contact form. Happy coding, and serialize safely!

Header image courtesy of Dan Morelle.

Edited to add, on 2018-07-09:

Astute reader Julian Coy writes that there’s another approach: you can use Django’s built-in serialization/deserialization framework.

This is particularly useful for smaller models, without lots of deep or crucial relationships. It looks something like this:

from django.core.serializers import serialize, deserialize

# Note that this requires an iterable, so you have to wrap your

# instance in a list:

json_version = serialize('json', [some_class_instance])

# Now you have a JSON representation of the instance that knows its

# own type.

# Put it on the wire here, passing it to a task or whatever.

# Then in the task:

deserialized_objects = deserialize('json', json_version)

# This will produce a list of DeserializedObject instances that wrap

# the actual model, which will be available as

# deserialized_objects[i].objectYou are keeping in mind that your data model and your Django Models aren’t the same, right? Django models are persistence-layer mappings that you can bolt some additional logic to. Your data model may be much more! ↩︎

A guide to using new color spaces & formats with OddContrast

OddBird’s color tool not only checks contrast ratios, but supports the new CSS color formats and spaces.

hint popovers, position-area and more

We have been busy updating the Popover and CSS Anchor Positioning Polyfills, but there is still more we can do with your help.

Display color gamut ranges and more

OddContrast, OddBird’s color format converter and contrast checker, gets new features – including the ability to swap background and foreground colors, and display color gamut ranges on the color sliders. Contrast ratios now incorporate foreground color alpha values.