Make the Web a More Colorful Place!

A guide to using new color spaces & formats with OddContrast

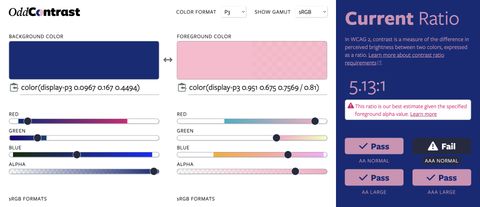

OddBird’s color tool not only checks contrast ratios, but supports the new CSS color formats and spaces.

API changes can be a headache in the frontend, but some initial setup can help you develop and adapt to API changes as they come. In this article, we look at one method of using OpenAPI to generate a typesafe and up-to-date frontend API client.

In initial prototypes, it’s easy for frontend devs to place fetch calls directly into a component. As app complexity grows, it becomes helpful to adopt a client pattern. This centralizes logic about authentication and API endpoints, and allows the developer to define reusable patterns for accessing and loading data. Often devs use something like Tanstack Query or RTK Query to define the patterns.

But problems can arise as changes are made to the API. Let’s walk through an example of how this plays out.

The backend adds a new field to the API representing a user’s full name, and removes the first and last name fields.

The API consumers (frontend devs) are hopefully notified of this change… hopefully.

The frontend dev adjusts the client to account for the change.

The frontend dev manually checks and updates all places where the fields are used, and catches everything… hopefully.

While centralizing logic in a client pattern can simplify the process of frontend changes, it still is error prone and takes time. These manually generated clients are incredibly helpful patterns, but contain a lot of boilerplate that is shared between each endpoint.

Luckily, I’m not the only developer wanting an easy abstraction of an API that I can use in the frontend. Of course, all of our APIs are written using different technology, and represent different content. This is where OpenAPI comes in.

You may have encountered OpenAPI through Swagger UI, but an OpenAPI spec of an API contains enough info to generate an entire frontend client for you. A good place to start is with openapi-typescript-codegen, which exposes each API endpoint and method as a function with typed inputs and outputs.

Depending on your tech stack, you may find a more specific codegen tool to create a client that integrates with React Query or RTK Query.

Once you generate the client, the code you need to call the API to create a user may just be:

const response = await UserService.userCreate({ requestBody: userInfo });A few things this provides:

userInfo means

no guessing if it’s first_name or firstName or just name.response mean you know what data to expect from the API.As an example, we recently needed to rename a field in a database from tag to

title to provide more clarity. Of course, we already had frontend UIs and

tests that referred to the tag field. I was preparing for a Find and Replace

marathon with lots of manual checks after the backend changes to the API were

completed. But when Ed, our backend developer on the project, pushed his

changes, he posted this in Slack:

Whoah, renaming Version.tag was so easy. Quick find and replace, run tests and linters, fix a few stragglers, and boom! Done with both frontend and backend in ~20 minutes and with confidence nothing is broken. Really proud of our CI today.

“Confidence nothing is broken” – I like the sound of that.

One challenge we encountered was considering what we should put into version control. In general, you want to keep compiled or derived code out of your git repo, as it can lead to gnarly merge conflicts and cause your CI to screech to a halt.

On the other hand, as we switch between branches for review and bugfixes, it can be a real pain to remember to regenerate the client when you switch branches.

After trying several iterations, we found a process that works:

When a change is made to the API, the developer generates a openapi.json

file with the changes, and commits it.

Our CI test suite verifies that the openapi.json file in source code is in

sync with the code.

The frontend client is generated from the openapi.json file as part of the

build step in CI and locally, and is not committed.

It’s important that these patterns are enforced by tests and CI, and integrated into our build steps. In addition, we have well-documented commands that run the necessary scripts.

As an added bonus, I’ve found it quite helpful in code review to be able to look

at the openapi.json diff in order to quickly understand what changes have been

made.

It would also be possible to not commit openapi.json to source control by

generating the frontend client directly from a running server. However, this

requires us to actually start up the server, which we don’t always want to do,

especially for tests in the CI.

I’ve generally found it easiest to use this pattern when the frontend and

backend are in the same repo. This helps keep things in sync and reduces merge

conflicts. If you have separate repos, treat the openapi.json and the

generated client as ephemeral. Instead of trying to resolve merge conflicts, opt

to find a pattern where you can quickly rebuild based on the server.

As we have this set up, we have simplified the “happy path” for API calls – that is, the calls that end in success. While OpenAPI includes the expected errors the API may return, I haven’t found a good way to surface that, or use types to confirm that I’m handling all cases.

For instance, take the unhappy path of a user who tries to verify their email for a second time. The API correctly reports an error, but this is a case where the user failed successfully, and it would be preferable to pretend it succeeded and direct the user to the login page.

The best solution I’ve found is to check that the error is an instance of the

generated APIError class, and then check against a string copied from the

openapi.json error example.

try {

await AuthService.verifyEmail({

requestBody: { token },

});

confirmSucceeded();

} catch (error) {

if (

error instanceof ApiError &&

error.body.detail === 'VERIFY_USER_ALREADY_VERIFIED'

) {

confirmSucceeded();

return;

}

showError("Uh oh! We weren't able to confirm your email.");

}In my dream scenario, I would be to get some error details from Intellisense,

and even be able to use a switch case to ensure I’m handling all expected errors

that are enumerated in openapi.json.

Creating your frontend client automatically from OpenAPI can make a lot of sense. With just a bit of setup, you can reduce boilerplate and get types for your inputs and outputs, allowing you to deliver functionality to your users more quickly and with fewer bugs.

A guide to using new color spaces & formats with OddContrast

OddBird’s color tool not only checks contrast ratios, but supports the new CSS color formats and spaces.

hint popovers, position-area and more

We have been busy updating the Popover and CSS Anchor Positioning Polyfills, but there is still more we can do with your help.

Display color gamut ranges and more

OddContrast, OddBird’s color format converter and contrast checker, gets new features – including the ability to swap background and foreground colors, and display color gamut ranges on the color sliders. Contrast ratios now incorporate foreground color alpha values.