This post is part of a series on revisiting fluid typography:

One thing I want to highlight

from the last several posts in this series

is that my solutions often involve

combining and comparing units.

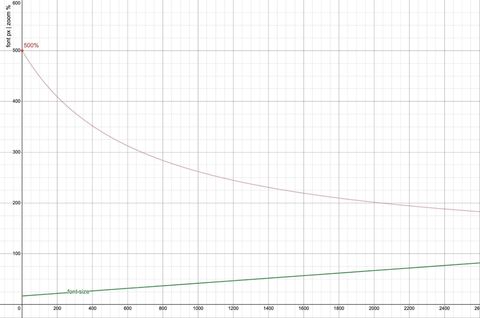

In the post on user font-size preferences,

I pointed out that em-based root font-sizes

multiply the user setting.

If we ask for a 20px font-size

by calling it 1.25em,

and then the user also asks for a 20px font-size,

the result will not be agreement

but a combined 25px font.

If we switch to a px-only approach,

we’re ignoring the user preference entirely –

which is even worse.

But if we stop doing the math in our heads,

and provide the browser with both units,

we can do a much more interesting

and useful comparison:

html {

font-size: max(1em, 20px);

font-size: clamp(1em, 20px, 1.25em);

font-size: calc((1em + 24px) / 2);

}

In all three cases,

there’s no conversion required.

We state clearly the px font-size we’re aiming for,

and then compare it against the user-provided em.

The units have different meanings,

and those meanings are useful

for expressing more clearly

the negotiation between site and user font sizes.

I like to think of relative CSS units

as browser-provided variables,

allowing us to pass in a multiplier.

We could write it out long-hand, if we had to:

html {

font-size: clamp(var(--user-font-size), 20px, 1.25 * var(--user-font-size));

}

Thinking about units that way

reminds me to think about the meaning

rather than the assumed px value of the unit.

Use the unit that means what you mean

Once I’ve handled that user-preference negotiation

on the root element,

I can refer to the result of that elsewhere

as 1rem.

In my mind 1rem is a always a calculation

with a variable in it:

calc(1 * var(--negotiated-base-font-size)).

Similarly 1em can be thought of as

calc(1 * var(--current-font-size)).

The difference between 1rem and 1em

is like the difference between --brand-pink

and currentColor.

Both are variables, both are useful,

but they describe entirely different relationships.

To ask which one is better in general

is an absurd question.

If I want to develop

fluid type calculations

that adapt to local context,

I’ll use em and cqi (container inline size) values.

If I want my calculations to remain consistent

across the entire page,

I’ll use rem and vi (viewport inline size) calculations.

In either case,

I’ll define those values on body

or other elements –

so that 1rem always refers to the

result of our initial negotiation,

and doesn’t take on more complex meaning.

How I handle spacing in CSS

It’s taken me a while to get here,

but this entire series was set in motion

by a great Ashlee Boyer article about

using px for spacing.

Her point is that users zooming in

care mostly about zooming the content –

and it can make things less readable

if we always zoom the spacing

at the same rate as the text (using em or rem).

We end up with excessive white-space

that pushes our content off-screen.

I think she’s pointing to a worthwhile concern,

but I came to a slightly different conclusion.

We don’t have to choose between px and em/rem

as our only sizing options here!

We can again

describe for the browser

how we think about white space

in more detail –

accounting for both font-size

and available space.

I actually use several different

‘spacing’ units in my work.

My favorite is the lh (line height) value.

When I’m putting space between paragraphs

or list-items in a flow of text,

I want to maintain a consistent rhythm –

so 1lh is the default,

and I can use multiples like

0.5lh or 3lh when I need some variation.

If I need this to be consistent across the page,

I can use rlh values instead.

But if I want to space things

on the inline axis, add gaps in a grid,

or put padding around a card,

I might also want to account

for the available space.

So now I’m negotiating two different concerns,

and I can represent each with a different unit –

using comparison and math functions

to get a final value.

Maybe one of these:

.card {

--min: min(1lh, 2vi);

--nearest-half: round(up, 2vi, 0.5lh);

}

If we know we want exactly 12px for spacing,

then absolutely –

just say 12px!

There’s no reason for unnecessary conversions.

But if we want to be responsive

to font-size and available space,

we can do that instead.

We could even clamp our responsive values

within a range of font sizes.

The right units

for any situation

are the ones that express most clearly

what we mean –

and sometimes what we mean

requires a combination of units.

This is the central premise of

the OddBird approach to

what we call

Poetic CSS Architecture.

There’s no best unit,

no best layout mode,

and no best selector.

When we use the entire language,

we have more tools for clearly expressing our goals.

If you enjoy Miriam’s writing

on modern CSS,

we offer

consulting and training

around Poetic CSS Architecture –

to help you eliminate technical debt

and build more performant

sites & applications.