This post is part of a series on revisiting fluid typography:

Earlier in the year,

I posed some questions

about how to approach fluid web typography

in modern CSS.

But I’m afraid I conflated several issues,

and failed to propose

any useful alternatives.

Now I’m trying to dive in,

split hairs,

and look for solutions.

The first post

was framed around fluid typography –

font sizes and scales

that adapt to the viewport –

but my primary concern here

has nothing to do with fluidity.

All major browsers

provide a default font size

of 16px as the basis for every website

to build from.

Users can change that value

by setting a global font-size preference

that will be applied to every website they visit,

CSS authors can choose to use or ignore that setting,

and then users can apply a site-specific page-zoom

on-the-fly if more adjustments are needed.

I want to explore all of those steps in-depth,

and consider how modern CSS might allow us

to improve on inherited best-practice.

Merging author and user preferences

For my eyes, on my laptop,

a roughly 20px font-size feels better

than the 16px browser default.

So it seems to me that I should set my

user preference to 20px,

and that change should

improve my experience of the web.

I don’t expect that I will see

exactly 20px fonts for everything –

and I wouldn’t want to!

- Not all content has the same needs.

When I’m reading a blog post

I like larger text,

but when I’m filling in a spreadsheet

smaller text makes sense –

as long as I can still read it.

There’s no preference setting

that will adapt perfectly in both situations.

- All styles are contextual,

and it’s the overall impact that we’re concerned with.

My

16px default size will look different

depending on the fonts used,

the space available,

the color scheme, line-lengths, white-space,

and so on.

- Fluid type is (by definition) a dynamic value.

If we want to integrate viewport units later,

we can’t do that while also matching

a user preference exactly.

So global preferences are limited,

and will never provide a perfect solution.

We need some way for authors to adapt those preferences

to be more appropriate for a given context,

and a page-zoom option for users

to make final adjustments on a site-by-site basis.

But the global setting should mean something,

and ideally it’s a value users are comfortable changing

to match their actual preference.

So the question for us as authors is

how best to interpret and adapt that preference

so that it is useful on the sites we build,

even when it’s not applied directly.

The current approach multiplies

Current best practice

starts with selecting an ideal pixel-based font-size

that we like for our site design,

and converting that to ems or rems

by assuming 1em = 16px –

the common default provided by browsers.

The result can be applied

on the html element with em

or on the body tag with rem.

Often,

this conversion is done in third-party tools,

but we can also do the math explicitly in CSS:

html {

--DEFAULT: 16;

--ideal: 24;

font-size: calc(var(--ideal) / var(--DEFAULT) * 1em);

}

Using that approach,

we achieve two important goals:

- We (as authors) get to choose

an ideal base size for our site content

(in this case

24px with units removed),

and it will apply for the majority of users

who never change their default setting.

- When users change their font-size preference,

our site text scales up or down

in relation to the preference.

- Users can also zoom in or out after they land on the page,

using built-in browser zoom tools.

We have some ability to establish a design,

and the user has some ability to adjust it –

both with immediate/local zoom,

and long-term/global preferences.

That sounds like a decent solution!

But if a site designer likes 24px fonts,

and I also (as a user) request a 24px default,

it seems like we should agree, right?

Instead, the approach above would give us

a 1.5em base-size (24 / 16 * 1em),

resulting in a (1.5 * 24) 36px font.

Was that adjustment helpful?

It’s not the font-size the designer wanted,

not particularly close to the

font size I asked for as a user,

and not a font-size that’s adapting to context

in some meaningful way.

Instead of merging our style preferences

to find the best fit,

we’ve multiplied them together.

It’s not the end of the world,

but it’s large enough to make me zoom out

every time I land on a page

that was designed to work perfectly for me already.

By setting a preference,

I’ve made a site that previously fit my needs less readable.

And that makes me very hesitant

to ever set a font-size preference.

Given that outcome,

I’m not surprised so few people change their defaults.

Still,

this is a much better solution

than simply overriding or discarding

the user preference.

It does allow me

to have some input if I need,

and I can make adjustments on the fly.

It’s not a terrible solution –

and for a time,

it was maybe the best we could do.

But it’s also not a great solution,

and I think we can do better.

Alternative 1 – trust the user

If we don’t need to control the font-size,

it’s fine to not set a font-size!

Adrian Roselli calls this

The Ultimate Ideal Bestest Base Font Size

That Everyone Is Keeping a Secret.

And I agree that it would be ideal

if more of the web

was built around user preferences.

I also think that 16px is too small

as a default in many situations –

but that’s not a problem.

In a world where most websites

respect my preference,

I can just change my preference

and get the result I want!

But that’s not the world we live in,

and doesn’t account for designer expertise

to help adapt our preferences into different contexts.

So maybe there’s a compromise solution we can find.

Alternative 2 – negotiate an average

In the original proposal

for Cascading HTML stylesheets,

Håkon Lie proposed a way to balance all style conflicts

between the user and author

through weighed averages.

Declarations can be marked with a percentage influence,

with users getting priority to claim influence first,

and authors left to distribute whatever influence remains.

If the user claims 100% influence,

their style is used without adjustments.

But if they claim 60% influence,

then authors can also weigh in with the remaining 40%.

The final result will be an average

of the two styles,

weighted 60% towards the user style:

html {

font-size: 24px 60%;

}

html {

font-size: 18px 40%;

}

html {

font-size: calc((24px * 0.6) + (18px * 0.4));

}

That part of the proposal

was later simplified to a

binary 0% (the default) and 100% (using !important),

so we no longer have a way to ask the user

for a weighted balance –

but we can still provide an average.

The user preference is represented by 1em here,

while the pixel value represents our site design:

html {

font-size: calc((1em + 24px) / 2);

}

That calculation gives us equal influence,

but we could also decide to

adjust the weighting depending on our design goals.

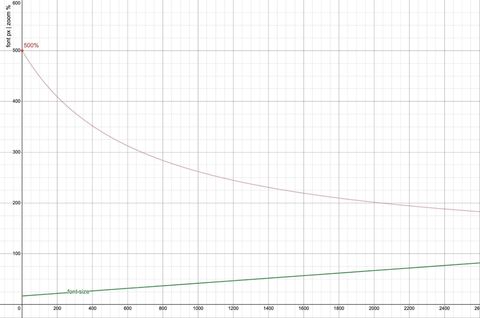

Here’s a playground to experiment

with different user and site settings,

at different weights:

See the Pen Weighted average font-size by @miriamsuzanne on CodePen.

In some ways,

I think this is the ideal solution –

it takes both the site design

and user preferences into account,

and finds a middle-ground between them.

But in the default case,

where no explicit preference was given,

the browser-provided 16px

is given a lot of (undeserved?) authority.

I also imagine site authors won’t be happy

with a solution that almost never

returns the value they selected for their design.

Is it ironic

that we ask users to put up with

a lack of exact control,

when we aren’t willing to do the same?

So much for user-centered design, I guess?

Oh well,

let’s try another approach.

Alternative 3 – larger value wins

Rather than thinking about the default setting

as a preferred text size,

we could think of it as a preferred minimum.

I imagine there are some cases where that assumption fails,

but in my experience

it’s a bit closer to the way people use font-size preferences.

Using the max() function in CSS,

we could set a site font-size to be used exactly,

unless the user has requested something even larger:

html {

font-size: max(1em, 20px);

}

That only allows the user preference

to increase our site font size.

We could switch to the clamp() function

if we also want to allow decreasing the default.

This solution gives priority to the site size,

while clamping our chosen value in a range

near the user preference:

html {

font-size: clamp(1em, 20px, 1.25em);

}

Those min and max values aren’t designed

to achieve a specific size –

it doesn’t matter if 1em here is

16px or 25px,

and we’re not doing unit conversion

to come up with those numbers.

The goal is just to keep us

close to the user preference on both ends,

with enough wiggle room to get our chosen output

in the default case.

We can adjust how tight the range is

by moving either the min or max closer or farther from

the user’s preferred 1em.

As long as our ideal font size is within range,

we stick with the size we brought.

But if the user preference is outside that range,

the font-size will scale to accommodate.

A 14px preference here will scale things down slightly,

a 20px setting won’t require scaling up,

but a larger preference will override us entirely.

We’re negotiating instead of multiplying!

Neither of these compromise approaches

are attempting to give the user exactly

the font-size they requested.

Instead, they are attempts to rethink

how a site design could best account for

changes to the user preference.

Both of these approaches feel like improvements to me,

because they negotiate some balance

rather than combining our overall offsets.

This morning,

Sondra joked

that our current team

has a combined 67 years working at OddBird –

which James points out

is older than NASA!

That number accurately accounts for each person,

and each year that we’ve been part of the team –

but simply combining all the values

doesn’t give us a meaningful result.

It’s more helpful to say that we’ve been on the team

for an average of 8 years,

and the majority of us have been on the team

for over 5 years.

The minimum is around 1 year,

but Jonny and I

have been doing this together for 17 years!

It seems to me that

the current font-size best practice

results in a similarly absurd ‘combined preference’ calculation,

and it would be more useful

to think in averages and ranges.

As an advantage,

these approaches leave any px-to-rem conversions

as a function for the browser to resolve –

rather than a calculation we need to pre-process.

If we have a (static) pixel value

that we’re aiming for,

that’s the value we provide.

Meanwhile em values remain relative

to the user preference at any size.

Rather than thinking of 2em

as a likely output of 32px,

I’m thinking of it as a math equation

with a variable and a fallback:

2 * var(--user-preference, 16px).

I use em when I care about relationships,

and px when I care about actual sizes.

To me,

that’s the fundamental rule of units in CSS –

we should say what we mean.

Are we allowed to use px values here?

We’ve generally been told

not to set our font-size in pixels,

because that would override the user preference.

But here the max() comparison

still allows our user

to override our static px value

when it gets too far from their preference.

As far as I can tell,

this removes the issue with px values

in font-sizes.

I’ve started using the max() approach

on html with new projects,

to handle the merging of user and site defaults.

From there,

I can use Utopia.fyi

(or similar)

to generate fluid scales on the body

which are based on the negotiated default.

The only issue I’ve had

is that I now need Utopia

to stop doing the em conversion for me.

But I’ll get into that

with the next article

on making it all fluid.

P.S.– Text-only zoom

Because a global font-size preference is limited,

the ability to make quick adjustments is essential.

No matter what my browser preference,

some pages that I land on

will need to zoom in or out

to work well for me.

That sort of adjustment generally requires browser UI –

some combination of page zoom

(available in most browsers),

and text-only zoom (only in some browsers).

Page zoom works by

changing the size of a pixel

so that everything scales at once,

while text-only zoom

only adjusts font-sizes,

without changing anything else.

I’ve heard a number of people suggest

that text-only zoom would be more useful –

if only browsers made it the default.

Richard Rutter also mentions this

in his reply to my previous article.

And I agree

that most of the time

I only need to zoom for text readability,

and it’s not necessary for

the entire layout –

along with white-space and images –

to zoom at the same rate.

But I don’t think

browsers can solve this issue on their own.

In fact,

I expect browsers are following our lead on this one.

Safari

and Firefox

both support text-only zoom.

Firefox requires a change in settings,

but Safari has a shortcut –

holding down the option key

while zooming

with command-plus/-minus.

Here’s a

test page you can play with

to see the difference:

See the Pen Zoom test page by @miriamsuzanne on CodePen.

Note that both page-zoom

and text-only zoom

behave the same (zooming everything)

if you toggle the switch for em-based layouts.

The same is true on most responsive websites,

including here on the OddBird website,

my personal website,

and Richard’s website.

Responsive web design

relies heavily on relative sizing,

so it makes sense that we’ve all made this choice.

Historically it was much more difficult

to mix fluid and fixed aspects in the same layout.

But even now it keeps things simple

and proportional

to size everything relative to the text.

A single bit of code

can be used to support both

zoomed-in and small-screen layouts.

I don’t know how much it matters.

Maybe this is also a best-practice

that we need to reconsider –

and stop building our sites

with fully font-relative units?

Or maybe it’s fine to leave things as they are.

But unless we make a change

to how we build responsive website,

I don’t see much reason for browsers

to prioritize text-only zoom.